(Aug 23rd, 2024)

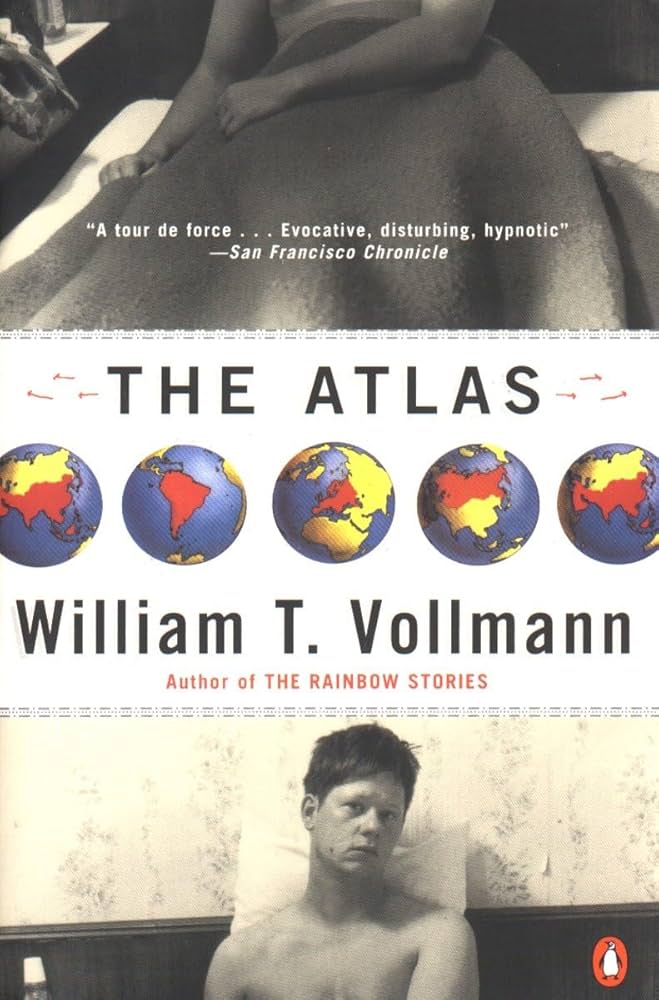

Mr. Vollmann has lived more life than probably any of us ever will. Based on both journalistic and personal travels, and rendered through an arcane, colorful lens, The Atlas charts life across six continents, and across many different kinds of poverty and desolation. This was my introduction to Vollmann’s work, and it feels like a representative work (based on what I’ve heard and read excerpted of his other writing)—so if one doesn’t know where to start, start here. There are many types of stories in here—whether conventional journalistic observation or poetic hallucination, barely recognizable as the place and time Vollmann attaches to the top of each section. Pet themes—prostitution, poverty, trauma, insanity, and faith—run throughout, and unite all manner of folk that the many narrators encounter. One’s enjoyment of The Atlas entirely depends on their ability to endure the whiplash from story to story, as the unintended consequence of Vollmann’s massive life experience, here recounted, is that you, as a reader, have no home. You will go everywhere, both geographically and otherwise, but belong nowhere. This can be exhausting when extended across nearly 500 pages, and with all the ascents and descents in style and tone that Vollmann endeavors. Many stories are almost entirely image-montages, describing a place and it’s particular brand of sadness and dead-end, without ever fixating on any character or focal point. At other times, Vollmann completely scrambles common sense, and introduces fantastical trips into his Atlas of the world, to dizzying effect. He turns a woman attempting a border crossing in Mogadishu to a phantasmagoric mess, with the woman multiplying into various clones, all while being observed by her lover (?) on an animated paper atlas. And this only lasting about 15 pages, and then we move on. Again, if you feel up to enduring these rapid changes in speed and focus, take a swing, because The Atlas can indeed be rewarding, if only in select places. For instance, the first story proper (“The Back of My Head”), set in a Sarajevo ravaged by the Balkan War, where Vollmann actually did reportage for Spin Magazine as a war correspondent, is a bravura way to open the collection. Vollmann is paranoid about being shot by a sniper the whole story through, and feels a continual itch “at the back of his head,” where he’s most worried about being targeted and shot. There’s a real sense of suspense, both for Vollmann, and for his companions in Sarajevo—fellow journalists and civilians alike. That two of Vollmann’s companions for Spin were actually killed by a landmine on May Day, 1994, with him being injured, only sharpens his teeth, and also his sadness, when retelling it for us. Other moments in the collection—those especially personal ones, including the poetic “Below the Grass,” about the accidental drowning of Vollmann’s little sister—deliver a similar jolt of reality. If one can endure, one should.

5.5/10